BBC News Mundo

¿Por qué hay tantas personas con discapacidad entre quienes mueren a manos de la policía de Estados Unidos?

Cientos de personas mueren cada año a manos de la policía en Estados Unidos y generalmente se le presta mucha atención a un detalle: la alta proporción de personas negras en esta estadística. Pero hay otra inquietante tendencia de la que rara vez se habla.

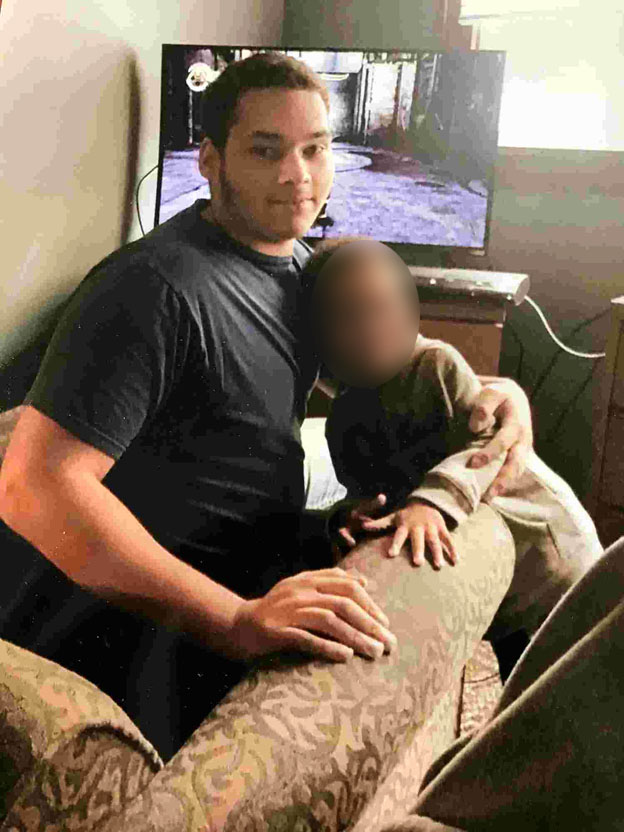

Poco después de las 05:00, tres policías de West Milwaukee, Wisconsin, irrumpieron en la casa de Adam Trammell, de 22 años. Un vecino les había llamado tras encontrarlo desnudo en el pasillo y hablando del diablo.

Los agentes lo encontraros de pie en la ducha, desnudo y desconcertado. Adam, a quien se le había diagnosticado esquizofrenia, estaba sufriendo una especie de crisis.

Según su padre, el joven tenía frecuentes delirios y alucinaciones, y ducharse lo calmaba cuando se sentía ansioso.

Adam no estaba armado y no parecía comportarse de una manera que supusiera una amenaza. Pero no salió de la ducha como le ordenó la policía.

Los policías dispararon 15 veces sus pistolas eléctricas, administrándole largas y dolorosas descargas eléctricas mientras Adam gritaba y se retorcía. Tras sacarlo en la bañera, le inyectaron varios sedantes.

Poco después, Adam dejó de respirar y murió en el hospital. Era el 25 de mayo de 2017.

El suceso fue captado por cámaras usadas por los policías.

"Casi no podía soportar verlo", le contó la madre de Adam, Kathleen, sobre la grabación al corresponsal de la BBC en Norteamérica, Aleem Maqbool.

"Estaba en su casa, no estaba en la calle, no tenía un arma. ¿Dónde estaba el peligro inminente? No había ninguno. No se lo merecía en absoluto ", dijo con lágrimas en los ojos.

Lo cierto es que la policía reconoce que Adam no había cometido un delito y no se sospechaba que hubiera cometido uno. Entonces ¿por qué sucedió?

La policía dice que irrumpieron en el apartamento solo para ayudar a Adam. Aseguran que lo hicieron para detenerlo y ofrecerle atención médica.

Ningún agente fue procesado. El caso no logró la atención de los medios de comunicación ni hubo marchas de protesta.

De este modo, Adam se convirtió en parte de una realidad de la que rara vez se habla: la alta proporción de personas con discapacidad entre los cientos que mueren cada año a manos de la policía estadounidense.

Algunas estimaciones sugieren que una cuarta parte del total de fallecidos tiene algún tipo de discapacidad, ya sea mental, intelectual o física. Pero otras investigaciones indican que la proporción puede ser mucho mayor.

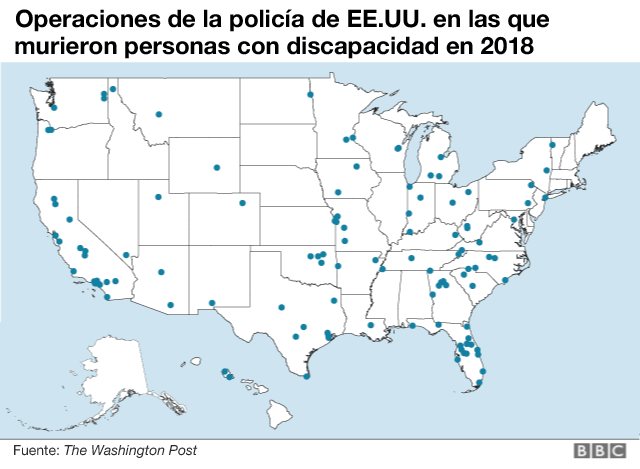

En lo que va de 2018, la policía mató al menos a 136 personas con discapacidad, según un recuento del diario The Washington Post.

En muchos países, la policía sería el último recurso para tratar con personas que atraviesan una crisis de salud mental, pero en Estados Unidos son a menudo los primeros en responder debido a la falta de agencias más especializadas.

Y aunque la historia de Adam pueda parecer extrema, hay rasgos que se repiten una y otra vez en diferentes casos ocurridos en el país.

Y cuando comencé a analizar estas interacciones entre la policía y las personas discapacitadas en diferentes partes del país, comenzaron a surgir patrones claros. La historia de Adam puede ser extrema, pero algunos aspectos se repiten una y otra vez.

Intertítulo

Ethan Saylor, de 26 años, tenía síndrome de Down. En 2013, fue al cine junto a su cuidadora en el condado de Frederick, Maryland, para ver la película "La noche más oscura".

Le fascinaron los personajes de la CIA, tanto, que quería volver a ver la película y se negaba a marcharse a casa.

Su cuidadora salió del cine a por su vehículo, pensando que el acercarlo al edificio le ayudaría a convencer al joven.

En ese momento, tres policías fuera de servicio que trabajaban como vigilantes de seguridad oyeron que alguien estaba en el cine sin entrada para ver la siguiente película.

Cuando le dijeron que debía irse o sería detenido, Ethan respondió que era un agente de la CIA y no se iba a marchar a ningún lado.

Mientras llamaba a su madre a gritos, Ethan fue sacado a la fuerza del cine y esposado.

"De alguna manera, Ethan termina en el piso boca abajo y sin respirar", contó su madre Patti. Los intentos por reanimarlo no funcionaron.

"El médico forense declaró que se trataba de un homicidio y que había muerto por asfixia", aseguró.

"Ese fue el momento más dramático y traumático de todo: el darse cuenta de que lo habían matado".

Según Patti, la policía e incluso algunas personas de su entorno dijeron que Ethan seguiría vivo si hubiera seguido las órdenes.

Pero ahí está precisamente el problema: su capacidad para seguir instrucciones. Ethan, como Adam, no tenía esta habilidad.

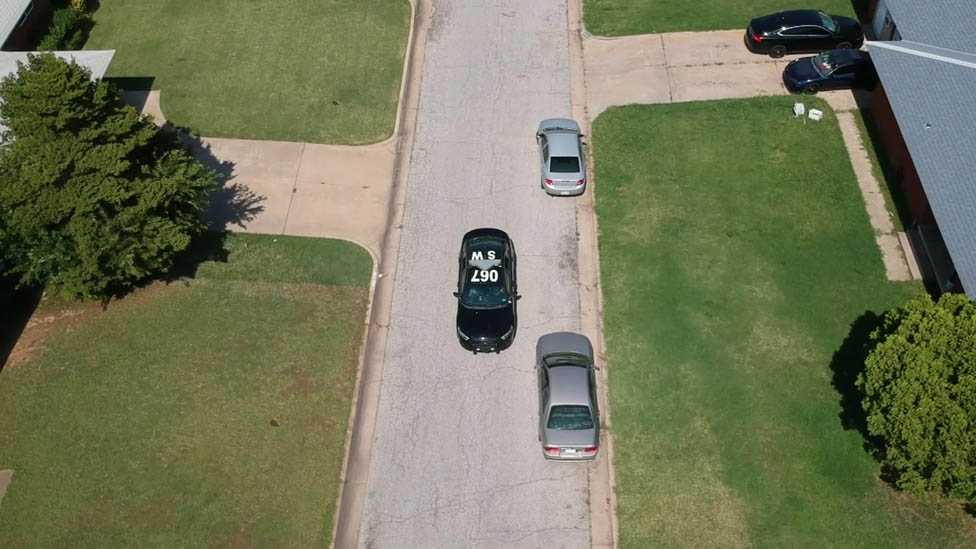

Este problema es aún más evidente en el caso de Magdiel Sánchez, un hombre de 35 años al que la policía se acercó en el porche de su casa en la ciudad de Oklahoma en 2017.

Los agentes creyeron que llevaba un arma (después se descubrió que era un trozo de tubería) y le gritaron que la dejara en el suelo. El enfrentamiento terminó con él muerto a tiros en su jardín frente a algunos vecinos.

Magdiel nunca escuchó las órdenes de la policía porque era sordo. En el momento, vecinos gritaron a los policías para hacérselo saber, pero dispararon igualmente.

"Era un chico con necesidades especiales, era sordo y era muy tímido. Era un chico mayor, pero era como un niño", contó Regina Smith, una de sus vecinas que vio el final del incidente desde su ventana.

"Me di cuenta de que era él y pensé: '¿Qué podía haber hecho?'".

"Nadie discute que los vecinos gritaron que era sordo", dice William Citty, jefe de policía de la ciudad de Oklahoma.

Pero defiende la actuación de sus agentes. "Él entendía que eran policías. Por eso llevamos uniformes".

Como en los casos de Adam y Ethan, ningún policía fue procesado en este caso.

El sargento Corey Nooner pasó por un suceso similar hace 15 años, cuando disparó y mató a una mujer que tenía esquizofrenia.

"Ella tenía un cuchillo y no respondía a mis instrucciones", dijo, asegurando que hoy actuaría de la misma manera. "Tengo que asegurarme que regreso a mi casa con mi familia por la noche".

"Cuando acabó el incidente, me dijeron que tenía un historial de enfermedades mentales. Entonces no lo sabía, y no entendía que pasaba", recordó emocionado y molesto por quienes aseguran que la policía estadounidense dispare a matar con demasiada frecuencia.

"¿A quién le gustaría pasar por algo así?".

Entonces, ¿por qué mueren tantas personas con discapacidad a manos de la policía?

Todos los agentes de policía de EE.UU, están armados. También existe la posibilidad muy real de que se encuentren con criminales que también lo están.

A lo largo del país, 40 agentes han muerto por disparos en lo que va de año.

So a large proportion of police training is geared towards the use of firearms and personal protection. But critics say this creates a police culture that is excessively confrontational, particularly in certain types of neighbourhoods.

An area that has seen a spate of disabled people killed in interactions with officers is Chicago's South Side - one of the most heavily policed areas in the US.

The complaint from many there is that officers too often employ a "command and control" style of policing, especially in low-income areas - shouting commands and physically dominating, particularly when someone doesn't immediately comply. This can sometimes, very quickly, lead the police to use guns.

The problem is - as we know from the cases of Adam, Ethan and Magdiel - that there may be reasons why it is harder for some people to comply with commands shouted at them.

Candace Coleman, who has cerebral palsy, is an organiser with Access Living, an advocacy group for people with disabilities. She grew up in the South Side of Chicago and works with people there who are disabled, particularly those diagnosed with schizophrenia and autism.

"If they do encounter police, it's a scary situation," she says, saying any confrontation with a police officer could lead to extreme panic and confusion in those with similar challenges to those of the young people she works with.

"'Who is this person with a gun?'", they might ask themselves, she says. "'Why are the lights flashing?' 'What are these loud sounds?'"

Being ordered to stand in a certain way - for instance, with their hands where they can be seen - or to look an officer in the eye can also be a problem, she says. So can being touched or grabbed by an officer. "If I'm not used to that, then I'm going to respond in a way that would look as if I'm being defiant," she adds.

That all rings true for Larry Trammell, Adam's father.

"There were times when you couldn't touch Adam," Larry says. "He [could get] really withdrawn or get excited, so I always knew when I dealt with Adam, I was to stay back and let him talk.

"If I went in there and just used my authority as a father and said 'You have to do this' - it just didn't work."

After weeks of trying, I finally manage to speak to the Milwaukee District Attorney, John Chisholm, who ruled Adam did not die as a result of the actions of the officers who used Tasers on him numerous times.

"They are not doing this because they wanted to harm Adam. It's the exact opposite, right?" says Chisholm.

"Their expressed intent, any number of times, is that they were there to help him. That they wanted to get him out of that situation."

I put it to Chisholm that they had, indeed, been saying that they wanted to help Adam, but they did so as they were issuing electric shocks - that they had their Tasers drawn even before they entered his home, even though he was in a building where others with mental illness lived. And I point out that the officers started Tasering him moments after the encounter started.

"Right, because they had to get him under control, so they could get him some medical attention," the district attorney repeats.

Lawyers for Adam's family highlight many other breaches of police guidelines that, for example, say someone should not be exposed to more than 15 seconds of cumulative electric shocks using a Taser.

They point out the terrible injuries, including broken ribs, that the post-mortem showed Adam had sustained.

The guidelines say that police encountering someone in a mental health crisis should "avoid increasing the subject's agitation or excitement, avoid physical engagement, avoid restraint and attempt to calm down the subject."

And yet the district attorney ruled that the behaviour of the officers had not been negligent or abusive.

"Not based on their training," he says. "The decision that they have to make is - what's the appropriate means to get him under control so that they can get him the medical attention at that point and time?"

Chisholm insists that Adam may have died anyway because of his health crisis - and that the officers' choice was either to do what they did, or do nothing.

"I would have liked it to have gone to trial," says Adam's father, Larry.

"If it had gone to trial and they had found the officers innocent, it still would have been hard, but we didn't even get that."

Police officers are prosecuted in very few cases involving the deaths of disabled people. They are presumed to have acted in good faith and often given legal protection on that basis.

Adam's case illustrates how police in the US are often called on to do a job that trained medical professionals would be far better placed to handle.

"Our calls concerning mental health from 2012 to 2016 have more than tripled," says Citty, Oklahoma City's police chief, whose officers shot dead Magdiel Sanchez.

"This society has not effectively dealt with mental health. They haven't provided the dollars for treatment," he says. "Officers are running from call to call to call dealing with this."

So if the police are to be the first to be called, how can things improve?

"I have to tell you, if you don't know someone with Down's syndrome, you are missing out," says Patti Saylor, Ethan's mother, as she trains a group of police officers in how to interact better with disabled people.

She is trying to turn the devastation caused by the death of her son into something positive, using her own horrific personal experience.

"Ethan didn't have the cognitive ability to recognise those officers needed an explanation," she tells the room. "Like, 'Officer it's OK, I'm going to sit in the seat and watch this movie a second time, my mom is on her way, she'll pay for the ticket when she gets here.' He didn't understand he should do that."

Patti tells me that she is sometimes struck by the level of ignorance about disability among officers, but that this simply mirrors the lack of awareness in society as a whole.

"I have been asked questions like 'You mean they are not all the same?' or 'So they are not out to hurt us?'" she says of officers she has trained.

Officers often apologise to her when they hear her story and display some degree of shame about what happened, she says.

But the Frederick County Sheriff's Office, whose deputies were involved in Ethan's death, has not engaged with Patti. It did agree a financial settlement with her but never apologised or admitted any wrongdoing.

Oklahoma City Police may defend the death of Magdiel Sanchez on his front lawn, but it is clear that the department has tried to make changes since the incident - offering more training to officers on how to approach disabled people.

The force deploys these specially trained officers to incidents where their skills will be useful.

One is Sgt Corey Nooner - the same officer who, 15 years ago, says he was forced to shoot and kill a woman with schizophrenia. That experience pushed him to try to understand mental illness better and he underwent a considerable amount of additional training.

I go out on patrol with him as he is dispatched to a home in an affluent neighbourhood in Oklahoma City.

A man has called to say that his wife, who has recently been discharged from a medical facility, is having a manic episode and experiencing paranoia and delusions.

At their home, Nooner patiently listens as the woman talks, visibly distressed, about how she is being watched by government agencies.

Ultimately, though, after she refuses to accompany him to see a psychiatrist and when she tries to dive into her bedroom, he restrains and handcuffs her.

Later, he tells me he had feared she might try to arm herself and that his basic police instincts kicked in.

For many, the nub of the problem is the way police are taught to interact from the very beginning - with so much emphasis on firearms training and personal protection, and relatively little on de-escalating confrontations.

As things stand, the deaths and injuries of people with disabilities at the hands of the police have left some of the people Candace Coleman works with in Chicago's South Side wondering who might be next, she says. Some of them have made pacts never to call the police under any circumstances, she adds, so worried are they that harm could come to them.

Coleman says they've also got together in groups to discuss what they can do to protect themselves in any interactions with the police.

"Extra disability training for police is one thing but is not enough," she says. "We need a cultural shift across the board."

"The way in which they approach situations needs to change. It shouldn't always be that the immediate reaction is to pull out your gun or your Taser or to yell or scream," she adds.

Until that happens, some of the most vulnerable people in US society will be left to work things out for themselves.